Fall 2020

Encounter

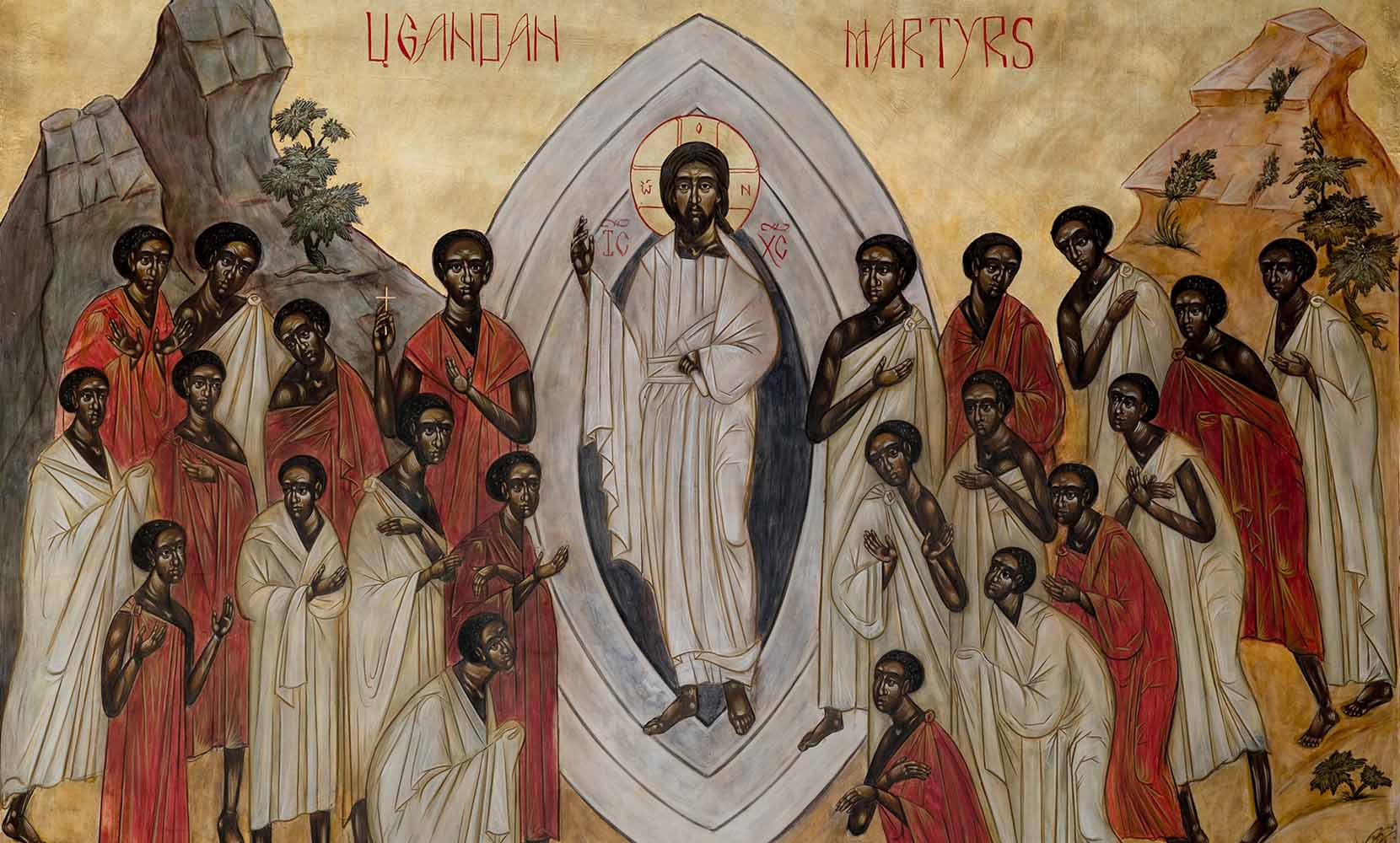

A personal reflection on the new icon of the Ugandan Martyrs commissioned for the chapel in Shipstad Hall.

- Story by Simonmary A. Aihokhai

Icon by Mary Katsilometes-Reinbold. Photographed by Bob Kerns

WHEN I LOOK at the new icon of the Martyrs of Uganda in the Shipstad Chapel, I immediately notice that the figures of Christ and the 22 Catholic martyrs are represented as Black persons. For those familiar with seeing the image of Christ represented as a white man, this image may be unsettling. But icons are meant to unsettle and surprise us. They are meant to mediate encounters between the viewer and the divine.

Allow me to share an example from my own experience of an icon that unsettled me and pushed me to new understanding.

Growing up in Nigeria, I never saw an image of Christ that spoke to Blackness. I never even knew I had internalized a Christianity that could not help me to appreciate my identity as a Black person until an experience I had in 2004. I have called this experience my graced-gift of rebirth.

The Los Angeles parish where I was working that year wanted to commemorate Thanksgiving Day by celebrating a liturgy that affirmed the different cultural realities of the parish community—68 countries in total, including my home country Nigeria. Through music and ritual symbols, we were going to be intentionally pluralistic.

As we processed into the church, my pastor informed me that he had placed an icon of a Black Christ on the altar to celebrate the few Black members in the parish.

Looking up at the altar and seeing the icon, I immediately uttered the words that came from my subconscious: “That is not Jesus. Jesus is not Black.”

I then realized that my microphone was on.

Members of the community heard me, a Black person, uttering these alienating words. Did I really mean that I couldn’t see myself, my Black identity, in Christ? Hadn’t I instructed people entering the Catholic Church for 19 years that we are all made in the image and likeness of God? Why couldn’t I see my Blackness in Him?

At that moment—my graced-gift of rebirth moment— I realized a hard truth: I had been colonized and not Christianized. My understanding of God prior to that moment was self-alienating. It never was able to make space for my very existence as a Black man rooted in concrete socio-cultural and political contexts.

“That is not Jesus. Jesus is not Black.” I then realized that my microphone was on.

I came away from this moment with new questions: What images do we have of God in our minds, and how do these images speak to us in the concreteness of our existence as creatures of history, context, and culture? I bring this question to my students all the time. I ask them: Who do your images of God include? Who do they exclude? And why?

The Ugandan Martyrs did not encounter a white God. Rather, they encountered a God who had become human like them in the very embodiment of their being as Black Africans living at a very precarious time in their collective history. Depicting the Ugandan Martyrs surrounding a Black Christ speaks of a Christ who finds Blackness as a worthy embodiment of the divine. For me, encountering this new icon, I am reminded that God identifies with all that it means to be Black in our world—then and now. This artistic representation of Christ as Black is most relevant for our times as our world grapples with systemic racism and how it has defined our collective imagination in ways that deny the innate human dignities of Black persons.

The Martyrs of Uganda: A Brief Ecumenical History

The new icon depicts the 22 Catholic martyrs of Uganda. But there are two other untold stories of martyrdom in Uganda (or what was then called the Kingdom of Buganda). Twenty-three Anglican martyrs died alongside the 22 Catholic martyrs between 1885 and 1886, and, ten years earlier, 70 Muslim martyrs were killed in 1875. Together, these martyrs of Uganda tell an ecumenical story of religious faith resisting oppression.

The martyrdom of the 70 Muslims is closely linked to the growing impact of Islam on the way of life in the Kingdom of Buganda. Islam arrived in Buganda centuries before Christianity through Swahili traders in East Africa and later through the Arab slave traders from the slave station of Zanzibar in the early part of the 1700s, after Zanzibar became part of the Omani Sultanate.

Islam became an intricate part of the cultural and social life of the Kingdom of Buganda, but Kabaka Mutesa I (1856– 1884), though converted to Islam, refused to embrace publicly a ritual custom—circumcision—mandated by Islam. Officials of his court wanted him to protect and preserve the primacy of African Religion. At this time the colonial interests of the British and Germans were taking shape in the region. Fearing the growing influence of Muslim Egypt in the region, Mutesa I suppressed all forms of resistance to his rule, even by his fellow Muslims. Thus, he ordered the killing of 70 Muslims who were the leading voices calling for his complete embrace of the ritual practice of circumcision.

To balance the power of religious and political influence in his kingdom, in 1862, Mutesa I admitted Christian missionaries and British explorer John Hanning Speke into his kingdom. The first batch of missionaries from the Church Missionary Society (Anglican) arrived in Buganda in 1877. Two years later, members of the Society of the Missionaries of Africa (Catholic) arrived as well. Court officials, along with other subjects of the monarch, embraced the Christian faith. In 1884, Mutesa I died, leaving his eighteen-year-old son, Mwanga II, as his successor.

Anyone who encounters this icon is invited to a deeper understanding of ourselves and our world.

Jesus Christ, as a historical figure, lived in Judea during the imperial domination of the region by the Persians, the Greeks, and eventually, the Romans. He had to navigate the realities that defined his society.

But to Christians, Jesus Christ also means more than the historical figure. Jesus is the gift for the possibility of new imaginations on how and what it means to be fully human in God’s world. To Christians, Jesus Christ, as enfleshed divinity, is an icon of God for all times. What God has become in the humanity of Jesus Christ is always revealing new ways of God’s interactions with creation. The humanity of God in Jesus Christ is an invitation to a new kind of encounter, one where we, too, are both sign and symbol of God, where we can embrace a new way of living in God’s world.

As I reflect on my microphone moment, I realize that this context was lacking in the way I was evangelized into the Christian faith. European and American missionaries, who evangelized many parts of sub-Saharan Africa during the era of colonial rule by the European colonial powers of the 19th century, had given me a rigid representation of Christ.

Though icons speak to us in our particularities, they also transcend them. In this transcendence lies the possibility for new imaginations and new encounters. While the icon of the Ugandan Martyrs showcases a Black Christ surrounded by Black persons, it cannot speak only to Black people. Anyone who encounters this icon is invited to a deeper understanding of ourselves and our world.

As we encounter this icon, let us be intentional in seeing how it invites us to open up ourselves to new horizons for inclusivity. As we celebrate our diversity, may we not also forget our oneness—Ut unum sint (“That they may be one” —John 17:21).

What is an Icon?

Icons are a hot topic in monotheistic religions because of the fear that they can end up becoming sources of distraction from the one God. Islam, for example, has always prohibited any form of iconic usage in relation to devotion to Allah, for fear that Muslims might fall into idolatry. In the Hebrew Bible, the second commandment specifically forbids the production and worship of images. But even with these prohibitions, Judaism is saturated with iconic representations of the unique relationship God has with the Israelites. For example, the Star of David, also known as Magen David in Hebrew, speaks of an iconic representation of God’s shield of protection over David and the Jewish people.

Christianity also struggles with a proper understanding of the meaning of icons. The fear of idolatry in the usage of icons within the Christian faith is real. Canon 36 of the Synod of Elvira (305–306 C.E.) specifically prohibits the placement of pictures in churches to ensure that they do not become objects of worship. Nonetheless, the usage of an icon as a medium for devotion has flourished in Christianity for millennia (in spite of the destruction of many ancient icons within the domain of the Eastern Roman Empire under the reign of Byzantine Emperor Leo III the Isaurian (717–741 C.E.)).

When I teach students about icons in my theology class, I often start with signs and symbols—how they mean different things and how an icon aims to be both sign and symbol. Both symbols and signs communicate and mediate meanings. However, a sign mediates meaning that is singular and thus predictable. Think of a traffic sign. There is only one meaning for a red light or a green light. A sign draws attention to itself and to its single meaning. God can’t be a sign alone, because God must always invite encounter with the divine.

A symbol, on the other hand, is saturated with meanings. With a symbol, there is always something new; there may even be an element of surprise. Theologically, symbols speak of the transcendent nature of God and of all that God has made.

Signs and symbols are not opposed to each other. They are two sides of the same coin. They both allow for relational encounters.

Christians believe God, in Jesus Christ, became human; God became both sign and symbol; God became an icon. We, as humans made in the likeness of God, are icons as well. All of creation is iconic, created for encounter.

The Martyrs of Uganda: A Brief Ecumenical History

The new icon depicts the 22 Catholic martyrs of Uganda. But there are two other untold stories of martyrdom in Uganda (or what was then called the Kingdom of Buganda). Twenty-three Anglican martyrs died alongside the 22 Catholic martyrs between 1885 and 1886, and, ten years earlier, 70 Muslim martyrs were killed in 1875. Together, these martyrs of Uganda tell an ecumenical story of religious faith resisting oppression.

The martyrdom of the 70 Muslims is closely linked to the growing impact of Islam on the way of life in the Kingdom of Buganda. Islam arrived in Buganda centuries before Christianity through Swahili traders in East Africa and later through the Arab slave traders from the slave station of Zanzibar in the early part of the 1700s, after Zanzibar became part of the Omani Sultanate.

Islam became an intricate part of the cultural and social life of the Kingdom of Buganda, but Kabaka Mutesa I (1856– 1884), though converted to Islam, refused to embrace publicly a ritual custom—circumcision—mandated by Islam. Officials of his court wanted him to protect and preserve the primacy of African Religion. At this time the colonial interests of the British and Germans were taking shape in the region. Fearing the growing influence of Muslim Egypt in the region, Mutesa I suppressed all forms of resistance to his rule, even by his fellow Muslims. Thus, he ordered the killing of 70 Muslims who were the leading voices calling for his complete embrace of the ritual practice of circumcision.

To balance the power of religious and political influence in his kingdom, in 1862, Mutesa I admitted Christian missionaries and British explorer John Hanning Speke into his kingdom. The first batch of missionaries from the Church Missionary Society (Anglican) arrived in Buganda in 1877. Two years later, members of the Society of the Missionaries of Africa (Catholic) arrived as well. Court officials, along with other subjects of the monarch, embraced the Christian faith. In 1884, Mutesa I died, leaving his eighteen-year-old son, Mwanga II, as his successor.

Mwanga II ascended to the throne of Buganda at a time when the European scramble for Africa was at full speed. Attempting to control the influence of Muslims, Anglicans, and Catholics in his kingdom, as well as curb the growing presence and power of the Germans and the British who wanted to take possession of his kingdom as part of their territorial possessions in East Africa, Mwanga II embraced a stricter policy towards his Muslim, Anglican, and Catholic subjects. He chose not to convert to Islam. His Muslim subjects began to reject his authority. His Christian subjects condemned his practice of polygamy, and his pages, who converted to Christianity, refused his advances. Fearing his loss of absolute authority in his kingdom, he decided to act decisively against all forms of perceived rebellion. From 1885 to 1886, Mwanga II ordered the killing of 23 Anglicans and 22 Catholics. The first to be killed was Joseph Mukasa, an Anglican, for opposing the murder of Joseph Hannington, the first Anglican Bishop of East Africa, who had entered the Kingdom of Buganda without the permission of the monarch and with the intention to evangelize. The youngest to die was the fourteen-year-old Kizito, who is among those depicted in the University of Portland’s icon. Most of the Christian martyrs—Anglican and Catholic—were ritually killed by being burned alive in the town of Namugongo on June 3, 1886. Even after their death, the tensions and power struggles between religions and colonial powers and African powers continued.

The Catholic martyrs were beatified on June 6, 1920, by Pope Benedict XV and then later canonized on October 18, 1964, by Pope Saint Paul VI.

The story of the Ugandan Martyrs, when told within the larger story of European imperialism and colonial ambitions in Africa, forces us to engage with the complex realities facing the continent of Africa. These martyrs were not just victims of anti-Christian sentiments; they were also victims of political and cultural struggles between the ruling class of Buganda and the European colonial powers.

As we reimagine what our country and world ought to look like, it is important that we intentionally embrace our diverse realities.

SIMONMARY A. AIHIOKHAI is an assistant professor of theology (systematics) at University of Portland. His research explores religion and identity; African philosophies, cultures, and theologies; religion and violence; comparative theology; and interfaith studies.