Fall 2022

A Sacred & Historic Space

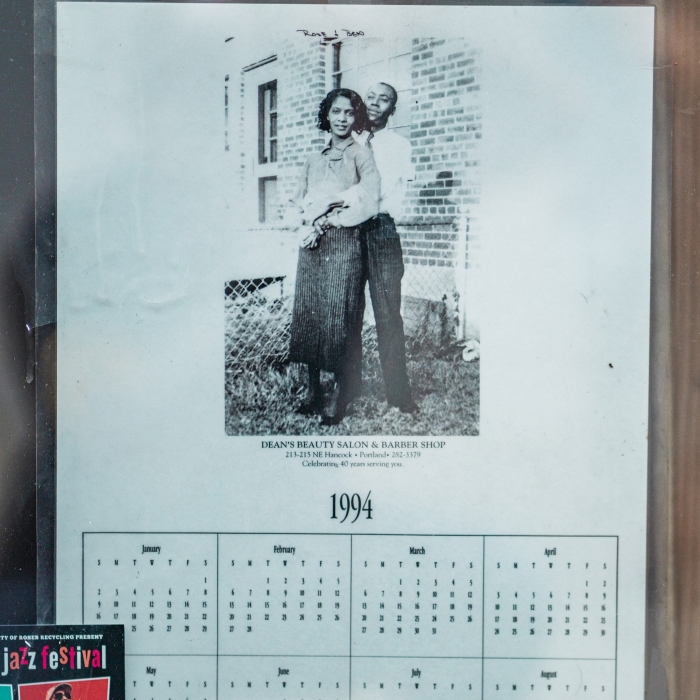

Dean’s Beauty Salon and Barber Shop was recently placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Founded by the parents of UP Regent and alum Kay Dean Toran, this business and its staying power tell a story about Black history—and Black success—in Portland.

- Story by Rosette Royale

All photos by Jesse Rowell Jr.

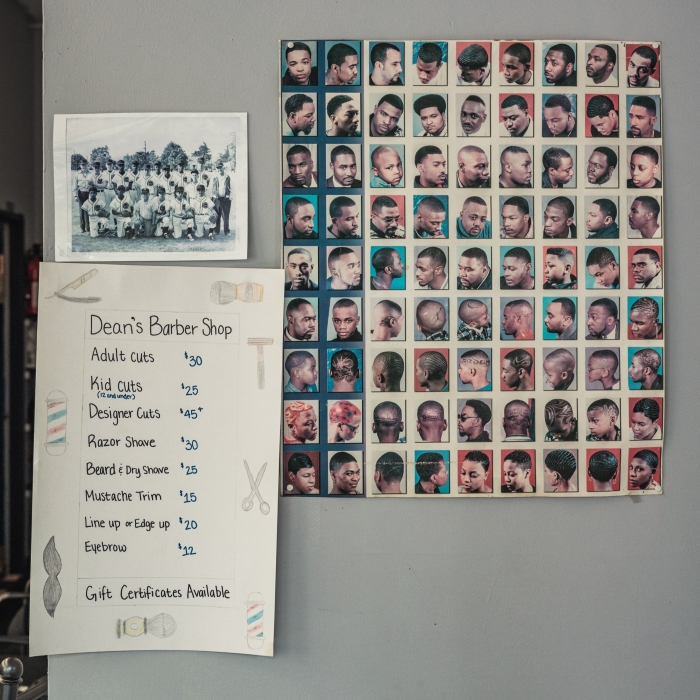

FIVE DAYS A week, the first customer usually rolls into Dean’s Beauty Salon and Barber Shop as early as 6 a.m., so it was no surprise that, by 10 a.m. on a recent Saturday, the shop pulsed with life. Near the front windows, hair dryers roared. Toward the back wall, water whooshed down a shampoo bowl, hairdresser-talk for the sink where clients get a scalp massage and hair rinse. In an adjoining room, barber shears buzzed, and over the speakers, old-school R&B singers crooned about love, family, and pride.

Amid the hubbub, Kimberly K. Brown chatted with her aunt Kay Dean Toran ’64. The pair discussed plans to meet in a couple days, but what went unsaid was what drew them there: Dean’s is a family business, one that’s occupied the same one-story brick building in Portland’s Albina neighborhood since 1956. It’s the oldest Black-owned salon in Portland, maybe even in all of Oregon. Brown and Toran have spent much of their lives inside the walls of 213-215 NE Hancock Street, growing up near barber brushes and pick combs, Marcel irons and hair clips.

Once they confirmed their plans, Toran left, the bell on the door ringing behind her, and Brown focused on straightening up her styling station. She kept at it for several minutes and then walked across the salon and tapped the shoulder of a customer who sat under a hair dryer. Brown lifted the dryer’s bonnet-hood that covered Janice Norris’s head.

“You’re dry,” Brown said. “C’mon.” She turned off the machine.

Back at Brown’s station, Norris sank into the styling chair. Shiny strands of her hair were wrapped around large blue rollers. Working gently, Brown pulled each roller free, and Norris’s hair sprang back and sat atop her head in shiny, dark brown coils.

“Make my curls look great,” Norris said.

Above her mask, Brown’s eyes focused, and, using a practiced, steady motion, she combed her fingers through Norris’s hair. The stiff curls transformed into soft, voluminous waves.

“You can see the color on the top and the edges,” Brown said. She gave Norris a hand mirror.

“It’s starting to look really cute,” Norris replied, admiring her reflection.

For several minutes after Brown finished, Norris remained in the styling chair as they talked about their lives. Part of their rapport came with the territory—“I talk for a living,” Brown joked. “I just do hair on the side.” But they share a long history, too: Brown has been doing Norris’s hair for thirty-eight years, longer than any of her other clients. And they go back even further. Brown’s mother used to style Norris’s mother’s hair. Now, Norris’s two daughters are clients. “One’s married, moved away,” Norris said. “But when she comes into town, she comes to Dean’s.” Her other daughter, who lives nearby, can come more frequently.

“They also come for the community,” Norris said, “where you can talk about, you know, what’s happening in the world, what’s happening in our cities.”

Ask anyone who comes to Dean’s to share their thoughts about what’s happening in the city, and they’ll tell you the same: Portland has changed. Of course, a similar claim could be said of just about anywhere. But what they see around Dean’s, in the place where they grew up, hurts. The gentrification, the dwindling number of Black homeowners, the hollowing out of community. The changes in the area, particularly around Dean’s, have been acute. Yet somehow, as rents have skyrocketed, as new developments have shot up, as neighbors have been forced out, as COVID-19 has stuck around, Dean’s has remained. How?

Perhaps it’s tied to the deep meaning barbershops and beauty parlors carry in many Black communities. “It’s a safe place for Black people,” Brown reflected, “but it’s also a very sacred place for Black women. It’s the only place we have that’s ours.”

This importance has been validated by the U.S. government. Earlier this year, the building that houses Dean’s was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In a 58-page application, a team of nominators asserted the site deserved designation because it not only represented “a financially successful Black-owned business,” but it had also embodied “a safe, welcoming gathering space for its clients within Lower Albina’s postwar African American community.”

Of course, in some historic places, history continues to be made—and, days later in Brown’s home, Toran, the unofficial family historian, shared how the shop that still runs today grew out of the dreams and determination of two modest people: her parents, Benjamin and Mary Rose Dean.

Kimberly K. Brown, owner of Dean's Beauty Salon and Barber Shop, at a customer appreciation block party this summer.

Kay Dean Toran '64 holds a photograph of her late parents, who started the business.

EVERY DREAM BEGINS somewhere, and Toran said the dream that led to a shop in Portland began in her parents’ hometown of Birmingham, Alabama. There, while a junior at A.H. Parker High School, patriarch Benjamin read about the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the momentous journey in the early 1800s from the Great Plains to the Pacific Ocean and back again. Clark’s descriptions of Mt. Hood and the Columbia River contained such beauty, they captivated the teenager. Benjamin told Toran that, at the time, he remembered thinking, “One day, I’m going to see that.”

His desire to travel out West gained traction in the early 1940s, when, in response to the United States’ war effort, construction mogul Henry J. Kaiser opened shipyards in North Portland, Swan Island, and Vancouver, Washington. When word of potential jobs in the Northwest spread to the Southeast, Benjamin sensed an opportunity for his wife and three children, the youngest of whom was Toran.

Job-based opportunities had long been on the mind of Mary Rose. She’d attended the same high school as Benjamin, where, along with learning about Lewis and Clark, students were taught the importance of Black people owning businesses. Mary Rose took that lesson to heart. A licensed beautician, she’d graduated from a local branch of the Madam C.J. Walker Schools of Beauty Culture, founded by the legendary Black entrepreneur whose business acumen turned her into the country’s first self-made female millionaire.

Toran said that, as a beautician, her mother “always believed she would be able to anchor the family’s financial resources on that Black business, while my dad had a job outside the home.” Not only did that job prove to be outside the home, it was also outside Alabama. Heeding the call he felt as a teen, Benjamin, in 1943, drove to the Northwest with Mary Rose’s sister and brother-in-law. They settled in Vancouver, where Benjamin began work as a shipyard welder. Several months later, Mary Rose and the children boarded a train and followed Benjamin to a place they’d never been.

While they may have been four adults and three children, the Deans and their relatives were part of a much larger exodus known as the Great Migration, a decades-long mass migration that transformed the country. From roughly 1910 to 1970, some six million Black people bid farewell to the South, with its devious, deadly Jim Crow-era practices, and set out for new frontiers, where they could soak up, as writer Richard Wright proclaimed, “the warmth of other suns.” Many chose New York City, Washington, D.C., Detroit, Chicago, even Los Angeles, where relatives had already gone. But some, like the Deans, didn’t follow others. They blazed their own trail and sought the “sun” of the Pacific Northwest.

Tragically, many of the millions who fled racism in one part of the country found it waiting for them elsewhere. U.S. Census figures reveal that in 1850, the year before Portland was incorporated, 821 people called the city home and only four of them were Black. Oregon became a state in 1859, and, in the years that immediately preceded its admission, racist policies of exclusion ensured few Black people would reside in the state. The result was clear decades later: By 1940, 305,000 people lived in Portland and only 2,000 were Black.

Even so, the sun’s warmth still broke through, thanks in part to the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. The Black population swelled. By 1944, more than 20,000 Black people lived in and around the state’s largest city.

For their first few years in the Pacific Northwest, the Deans lived in a wartime housing project in Vancouver called Bagley Downs. Then the family moved into Portland, where Benjamin worked as a janitor at the Federal Reserve Bank, while Mary Rose, licensed in a new state, did hair. By devoting one salary to cover expenses, they were able to dedicate the second salary to savings. They used those savings to buy a house at 121 NE Hancock Street (Mary Rose’s sister and brother-in-law settled nearby). The house, which came furnished and included an upright piano, cost $950. They paid for it in cash, said Toran. Mary Rose opened a beauty salon in the basement, and Toran remembers the salon floor being lain with linoleum. “It was a one-chair shop,” Toran said. “That’s where she really built the business.”

Proudly Christian, Benjamin and Mary Rose were also diligent, and they worked hard to overcome everyday obstacles to ensure a strong and secure future. The parents continued to put aside one of their salaries, and years later, they dipped into those savings again to buy a smaller house next door. Their second house cost $250. To the east of that second house sat a vacant lot, which seemed the perfect place for a stand-alone shop. But purchasing a vacant lot and paying to construct a building on it was significantly more expensive than buying land with a completed house. Who, they wondered, would offer a business loan to a Black family so they could fulfill their dream?

IN TRUTH, BY the time the Deans moved into Portland, their options for where they could live and buy property were already limited. Not long before their arrival, in the 1930s, a new program offered government-insured mortgages to homeowners across the country, with the aim of forestalling a wave of foreclosures that might follow the Great Depression. And it worked—but over time, the parameters outlining who qualified for those mortgages became more restrictive. The federal government established the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, which created color-coded maps to depict the perceived financial risk of an area. Areas believed to be the most financially risky were designated in red: a practice now known as redlining. Many redlined areas were neighborhoods where Black people lived, which destroyed the ability of countless Black families to acquire mortgages.

One area in Portland open to Black homeowners, and therefore the Dean family, was Albina. Housing stock in this section of northeast Portland was tight—and became more so after May 1948, when a flash flood in nearby Vanport, the country’s largest wartime housing project and Oregon’s second most populous city, displaced thousands of Black families. Many migrated to an already crowded Albina.

Yet even as the area served as the cradle of Portland’s Black postwar community, families still found their entry into the neighborhood blocked by discriminatory practices. Aspirational homeowners sometimes pursued alternative means to obtain properties, such as tapping a white acquaintance, someone they may have known through a job or family connection, to act on their behalf. In such a scenario, a white person would buy a home, then sell it directly to a Black family they knew. Yet procuring a bank loan to purchase a lot and construct a building, even for a working-class Black family like the Deans, who already lived in Albina, was trickier.

This reality did little to deter the family, even when the bank Benjamin frequented denied his loan request. Instead, he and Mary Rose discussed their plans. He spent his nights in the family’s dining room, drafting blueprints for a future shop two doors down, while Toran watched, fascinated. When she eventually asked where he learned drafting, his answer was swift. “Parker High School taught us everything,” he said.

And perhaps part of that “everything” was to be alert for opportunity. As Mary Rose continued to see customers in the basement salon, Benjamin, by then a licensed barber, cut hair at a nearby barbershop. One day at work, he noticed a flyer on the floor advertising business loans. After being rejected by his own bank, could this be the help they needed? Benjamin followed his intuition and took his blueprints to the loan office on the flyer, where he was asked to fill out an application.

Benjamin knew that to list both Dean family homes was a risk, because if something went wrong with the loan, his family could lose everything. He made a calculated decision: He’d only list one property. Of course, this wasn’t the whole truth, but with nowhere else to turn, he needed to ensure that his family always had a home.

When the loan officer asked if the application contained all current properties, Benjamin said yes. They agreed upon a $10,000 loan with a two-year repayment plan. And with that, the officer approved the application.

Then the officer told Benjamin he knew Benjamin owned a second house; he knew Benjamin had withheld that information. But the officer said he understood why Benjamin had made that choice. He shared that in his tradition—he was Jewish—safeguarding the family was paramount. “I knew you were protecting your family,” the officer said. “And that is the reason why I know you will pay this loan back.”

This was a story Benjamin told to everyone, Toran said, as a way of showing how people of different races and faiths could work together to improve lives and strengthen communities. Benjamin had been aware that Black and Jewish people had often been allies in the fight for civil rights. Now that allyship was personal. He and Mary Rose worked tirelessly to pay off the loan in two years.

But now that they had a loan, they had to build the salon. “My dad and my mom knew that to get this together,” Toran said, “to be able to do this, they were going to have to rely on the Black professionals in our community.” They called on an electrician, a plumber, and others. By the time the wires were run, the water line connected, the fixtures complete and the styling chairs set in place, it was 1956—and northeast Portland had a new Black hair shop.

While it’s customary now for anyone to enter a unisex salon, during that era, barbershops and beauty salons did not share spaces (whether this was due to local regulations or social customs isn’t clear). To accommodate this practice, the building’s interior was split in two, with barbershop clients entering through the west door and salon clients through the east. (An interior doorway adjoining both spaces was constructed in 1977.) Outside, a sign projected from the front brick wall: Dean’s Barber Shop Beauty Salon.

DEAN’S LOCATION PLACED it in the heart of a thriving Black neighborhood, and within walking distance were grocery stores, a tavern, a nightclub, a BBQ joint, a doctor’s office, even a funeral parlor. Business boomed. At the shop’s peak, Mary Rose had three beauticians working for her, and Benjamin had the same number of barbers working for him. Toran recalled it was a well-known neighborhood gathering spot. “It wasn’t like church, and it wasn’t like a party,” she said. “It was a place to go: the center of attention in Northeast Portland.”

Life, and business, flourished. The Deans were now raising four children. Mary Rose and Benjamin took their family on day trips to the Pacific coast; they drove cross country to visit relatives in Alabama and see other places with vibrant Black communities, Toran said.

As she continued recounting her family’s history, her older sister and Brown’s mother, Gloria, entered the room and listened in. Gloria didn’t speak, but her eyes sparkled and grew moist as the tale unfolded.

Seated nearby was Brown, who remembered being young and taking some of those cross-country journeys with her grandparents Benjamin and Mary Rose, whom she called Papa and Nana. Brown said Mary Rose wanted them to witness Black folks creating success all over the nation. “It wasn’t just Portland,” Brown’s grandmother reminded her. “[There] was the surrounding world, the surrounding country where Black people were doing as well or even better.”

Though in many places, some Black people struggled. Back in Oregon, Benjamin visited Black prisoners in the state penitentiary, and when some obtained a barber license while incarcerated, he hired them after their release to work at Dean’s. On numerous Thanksgivings, Toran said it wasn’t unusual for unknown people to be seated with them at the table. If a Dean child asked why, Mary Rose would reply, “They didn’t have any place to go.”

When it came time for Toran to consider where she’d go for college, she felt drawn to Howard University, a historically Black university in Washington, D.C. With Howard being so far away, her parents suggested an alternative: If Toran attended school for two years in Oregon, they would cover her tuition; then she could go wherever she wanted. Toran agreed, and following in her brother’s footsteps, she attended the University of Portland. There, she bonded with other Black women students and relished the open debate in classrooms. Instead of staying two years, she graduated four years later with a B.A. in liberal arts with a focus on sociology, psychology, and philosophy.

But change was inevitable. Transportation and urban renewal projects displaced countless Black residents in Albina. Shops closed; neighbors left. Through it all, Dean’s hung tough. Then in 1979, Mary Rose passed away. By this point, Benjamin was semi-retired, and the beauty parlor’s operation was transferred to Toran’s older sister, Gloria (she smiled when she heard her name mentioned). After Benjamin’s death in 1996, Gloria ran the entire business. When she could no longer run the shop, Dean’s was taken over by her daughter Brown.

Toran said that, seen through the lens of history, the shop stands as the personification of her parents. “That’s what the shop says to me today: That they realized their dream and it lives today.”

Brown agreed, adding that her grandmother stressed not only a sense of ownership in the business, but also the need for its continued stewardship. “She would say stuff like, ‘Well, you know, this is your shop. This is the family shop,’ ” Brown recalled. “ ‘You have to take care of this right here, because this is who we are.’ ”

THAT SENSE OF caring had been evident in the shop days before, on that active Saturday morning.

After Brown had finished the hair of her longest client, she turned to her next customer, Sharon Nickleberry Rogers, who sat under another hair dryer. Rogers has a standing appointment, every other Saturday, 9 a.m. As soon as Rogers sat in Brown’s styling chair, she and Brown started talking, the conversation flowing as it shifted topics: paying for overpriced plane seats, racist movies, watching racist movies while sitting in overpriced plane seats, Covid. They discussed a local chef who planned an event to honor Juneteenth, the recently designated federal holiday that commemorates June 19, 1865, when enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, received word they were free, two years after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. The event was called “Feed Black Portland.” Oxtails were on the menu.

Rogers estimated that she and Brown have known each other some 50 years, since the third grade. She has been coming to Dean’s for decades, and when she thought about the gentrification that’s gripped the neighborhood, the loss of generational wealth, she shook her head. “Today, you can’t afford to buy a house in northeast Portland,” Rogers said.

Yet northeast Portland is where Dean’s sits, so she returns to this brick building in this section of the city every other week. For as long as she can remember, Dean’s has been a pillar in the community. “It’s nice to know it’s still here,” she said.

Once Rogers left, it was Brown’s turn to get her hair done. She was heading to a baby shower for her second grandchild, and she wanted to look nice. Brown left her styling station and sat in Sylvia Riley’s chair. Riley has worked at Dean’s for 15 years. Riley’s specialty is braiding, and while Brown had tended to Rogers, Riley had braided someone’s hair with a speed and dexterity that seemed implausible (“It’s not in your wrist, it’s not in your arm, but these three fingers,” she’d explained, wriggling her thumb, pointer, and middle fingers). But Brown didn’t want braids. She wanted waves.

From a canister at her station, Riley pumped out a dollop of foam wrap, a liquid settling lotion that turns to foam when aerated. With her left hand, she spread foam on Brown’s hair; with her right, she used a white, fine-tooth comb to contour the damp hair. The two talked about the baby shower and within 15 minutes, Brown’s hair was a study in geometric principles, a coiffure constructed of uniform, rippling waves.

Brown stood up from Riley’s chair. She gathered her items. Soon, she’d be with family, though being in Dean’s, she knew, was being with family as well.

“It’s like I tell people all the time,” she’d say later. “When I walk in the shop in the morning, first thing I do, I say, ‘Hey, Nana and Papa. Thank you for looking out for the shop for me.’ Then I keep it moving.”

And even as change moves the world around the shop, Dean’s won’t be moving from its spot anytime soon.

ROSETTE ROYALE is a Seattle-based writer and storyteller who focuses on stories of culture and place. He’s working on a memoir about being a Black queer person who goes bushwhacking in the Olympic temperate rain forest.

More Stories

The Making of a President

Robert D. Kelly, UP’s 21st president, comes to the role with faith, experience, and hope for transformation.

- Story by Jessica Murphy Moo