Summer 2022

What One Person Can Do

Delivering medical supplies to Ukraine renewed her faith in humanity

- Story by Danielle Centoni

ONE EVENING THIS past April, Alena Romanyuk stared into the darkness of her lodgings in Lviv, Ukraine, her jet-lagged body heavy with fatigue. She had traveled more than 5,000 miles over the past 30-some hours, switching between cars, trains, planes, and a cargo van with almost 800 pounds of medical supplies in tow. She wanted nothing more than to sleep. And she might have, but the air raid sirens started at 10 o’clock.

“I was lying there, so tired, and I just thought, ‘If this is my time to die, I guess it’s my time.’ I just had to release control.”

This was Romanyuk’s first night back in her native Ukraine in three decades, a surreal sort of homecoming. For the next seven days she would have to trust a network of strangers to transport her, pass impromptu quizzes to prove she wasn’t a Russian spy, and download an app that located missiles in the area. Still, after weeks of watching the war unfold on the news, she knew she’d made the right decision to travel there to help.

“It hit home because it’s my people,” she says. “It was exactly thirty years ago almost to the month when my parents came to the US from Ukraine in 1992. I could have still been there. Who am I to have this privilege and opportunity? I can give back. I’m a trauma nurse. I speak the language. I can get the supplies.”

Romanyuk, who graduated from UP’s School of Nursing in 2009, doesn’t want to be called a hero. But it takes a heroic dose of bravery to fly across the world and enter a war zone all by yourself, with no previous wartime experience or institutional backing.

That doesn’t mean she wasn’t scared. “What if I don’t come back?” looped over and over in her mind. “I was so anxious the whole time I could barely eat,” she says. “I was trying to be strong. I can’t show my fear because the people there are already scared. But it was amazing to see their bravery and resilience. Not once did they complain. They’re like, ‘This is what we have to do and we’re going to push forward.’”

So that’s what she did too. For eight days she surrendered to the chaos and uncertainty of war and went wherever she was needed, from training civilian fighters on how to apply tourniquets to providing translations for Ukrainian refugees at the Poland border.

“You know when a trip just works out? You feel like you’re led by a greater force,” she says. “Everything just worked out every day.”

That her trip went off without a hitch feels like something of a miracle considering Romanyuk was traveling solo, which wasn’t her original plan. She works as a trauma nurse and coordinator in the ER at Emanuel Hospital in Portland and had first reached out to Medical Teams International to offer her services. But they required a minimum commitment of two weeks. She was only able to get nine days off work, but she was determined to figure it out.

She got connected with the daughter of a medical director in Ukraine who gave her a list of what was needed most, things like tourniquets, QuikClot, chest seals, and combat gauze—trauma supplies that are in great demand and costly. “These civilians going out to fight have nothing on them,” says Romanyuk. “They’re going out to war with Band-Aids.”

She posted messages among her network that she was seeking donations of supplies, or money to buy them, and word spread. A paramedic group in Bend donated fifty Stop the Bleed kits. A yoga studio in Hood River donated mats for refugees to sleep on in shelters. A friend got the bright idea to call the airline and ask them to waive the baggage fees.

“It was so heartwarming to watch people coming together, the ripple effect of people doing good things,” says Romanyuk. “People see you doing something and ask themselves, ‘What can I do?’ That’s the message I want to spread: What can you do with the resources you have to change someone’s life?”

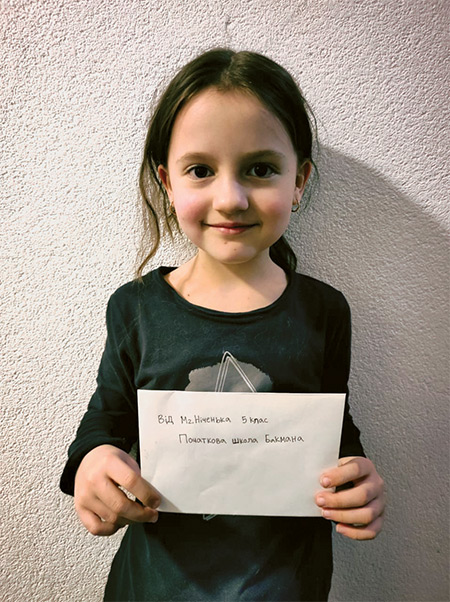

Her trip even gave a fifth-grade class at Buckman Elementary the chance to learn one of life’s most important lessons: There’s always something you can do.

“When my friend’s daughter found out I was going, her class made cards for Ukrainian kids written in Ukrainian.” With messages like “We stand with you” and “We believe in you,” the cards she passed out to children staying at a Ukrainian refugee center let them know their peers in the US were thinking of them. She took videos and pictures so the students back home could see the impact they made.

“It helped with morale. They were like, ‘You came all the way from the US?!’ It brought their spirits up. It was a boost of morale.”

In one-and-a-half weeks Romanyuk had packed up fifteen giant bags with 780 pounds of life-saving gear that she would personally deliver directly to the people who needed it—which is especially notable considering how difficult it is to get shipments into Ukraine. She also had $25,000 in funds left over to donate to the refugee center. “There are twenty-thousand people being housed there. The people still in Ukraine are struggling. That’s where the biggest need is.”

But the supplies aren’t worth much if people don’t know how to use them, and that’s where her thirteen years of nursing experience proved invaluable.

Still, in Ukraine, it felt different. “When you’re in the hospital and you teach people, maybe once in their life they’ll do these things with a team in a secure setting. But there, the weight it held…that was the most memorable thing for me.”

As dangerous and difficult as it was to travel to Ukraine alone, Romanyuk says, looking back, she wouldn’t have wanted it any other way. “I was able to meet people and put myself in situations that opened up so many more avenues. Talking with civilians and hearing their stories, nothing beats that human connection. Now that I have these connections with people, I’m sending more supplies. I can still be this channel of giving for the community around me.”

And she knows from experience that the effects of making those personal connections will linger long after the last dollar is spent. “When I went to UP, I received one of the Ralph and Sandi Miller scholarships for naturalized US citizens. They took the recipients out to dinner, and we’d also have dinner with them for Founders’ Day. It was very personal. I remember him saying, ‘I’m giving back because of what I was able to do with what I was given, and I hope in the future you’re able to do the same.’ That idea of giving back to each other instilled a sense of community.”

Working in an ER is challenging even in the best of times, but add in a pandemic and it’s been a rough couple years for nurses like Romanyuk. In many ways, the trip renewed her faith in the power of community, from the way both friends and strangers in the US worked together to get her funds and supplies, to the way strangers became her trusted friends in the midst of war. “Going there made me believe in humanity again,” she says. “There are good people that still care about humans and want to help each other. It shifts your perspective on what’s important in life: the people around you and the good you can do with the resources you have.”

The hardest part, she says, is holding onto that faith even when despair about the scope of the crisis starts to creep in. “It was really hard to come back. It was hard to talk about it,” she says. “It’s good to know I did something, but it can feel defeating because there’s so much work to be done.”

That’s when she remembers the important advice she received from a colleague, a trauma surgeon who has experience in the military. “He said, ‘You need to go in with the mindset that if you teach someone CPR or how to apply a tourniquet, they’ll teach someone else. Think of the ripple effect of your actions—what you leave behind that continues to manifest. Even though you’re not there, your work continues.’ That’s what I hold on to. It’s amazing to know what one person can do.”

DANIELLE CENTONI works in UP’s marketing and communications department.