SUMMER 2023

The Central Motif

Dedicated to Fr. Tom Hosinski, who taught us to see the spirituality within the science.

- Story by Lars Erik Larson

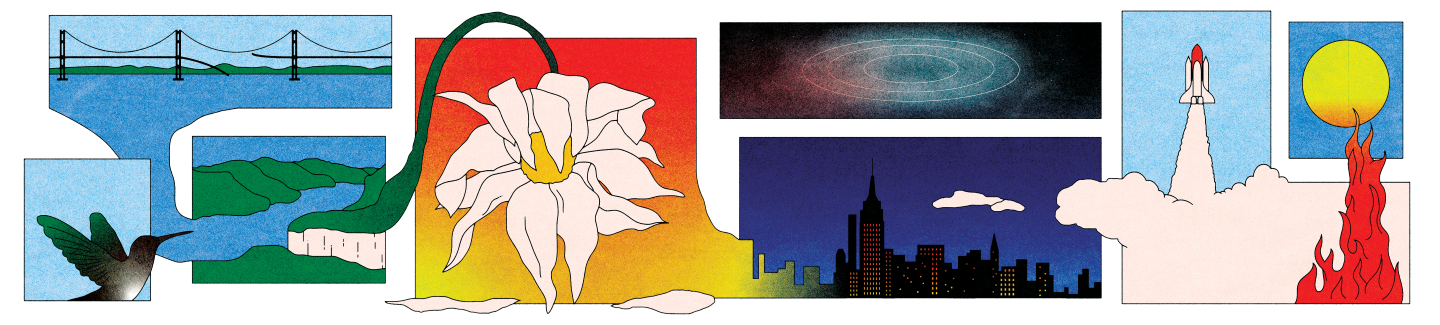

Illustration by Allie Sullberg

NOT LONG AGO I read that around fifty percent of human conceptions fail in the womb. In most cases, this happens not long after a sperm hits an egg. A cell divides, multiplying into biology’s stunning geometries, and then, just as suddenly as it started, it stops. Fifty percent—it’s hard to imagine. For every person an unborn sibling.

I can’t seem to shake facts like this these days. Maybe it’s just the view from late-middle age, but everything’s been funneling back to the idea of failure. As a professor of literature, I’ve been trained to believe that patterns point toward truth. But what truth is revealed by a pattern such as this—that we’re as likely to be born as to fail to be?

Back in my thirties, my friends and I didn’t know what a miracle a healthy birth was. In time, though, friends and family have related their stories of miscarriages, how the discovery of the latter would come in an indelible moment: a realization the day had passed without the presence of kicks, a wrongful bead of blood, an ultrasound technician frozen for a minute at the screen before excusing himself to find the doctor. We hugged each other in silence and felt like nothing could ever be made right again. And even though many of us were ultimately blessed with children, decades later, we’re still haunted by those children who might have been. What was the truth at the heart of these losses? Is there any solace at all in finding and tracking patterns of failure?

WALKING AROUND CITIES I’ll sometimes look up and marvel at the buildings and bridges, all the feats of human engineering. These creations always give me hope. What a boost—for a creature the size of a shrub—to be able to stretch arms as wide as the Golden Gate, to stand as tall as Dubai’s Burj Khalifa.

But the strongest human inventions fail, too. Devastating disasters haunt our memories (an exploding Space Shuttle, a collapsing condominium, a wobbling Tacoma Narrows Bridge untwisting itself into the icy Puget Sound). The nightly news awaits the next collapse.

Engineering writer Henry Petroski insists that the periodic failure of human structures does more to advance our world than any number of successful inventions. Each fresh failure breeds an innovation: the tenement fire that sparks mandatory fire escapes, the cracked interstate bridge that prevents scores of future ones, the slipped skywalk that ushers in the use of steel bolts. Failure, in the long run, lessens failure—leading Petroski to propose, “The question, then, should not only be why do structural accidents occur but also why not more of them?” I hear a kind of optimism in the question—though the potential of the next collapse gives me pause.

HUMAN CULTURE HAS long offered models for imagining this connection between creation and destruction. Hinduism’s Shiva is the god of destruction and rebirth. The Bible’s God swears off destruction by flood and starts anew with his iridescent creation (still leaving the threat of fire next time). The world’s reigning economic system of capitalism was famously defined by Joseph Schumpeter as “creative destruction.” Even evolution, as it unfolds a staggering variety of life-forms, allows the failure of most of those creations. (As Annie Dillard insists in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, “Evolution loves death more than it loves you or me.”)

I can feel my middle-aged vantage point at work: a body I can already feel going out of tune; dreams that I now know will go unrealized; a coat and tie now used for more funerals than weddings. Are these new developments failures? I admit that a part of me believes they are, even if they are part of an overall design.

I’VE FOUND SOLACE in wilderness. The age and solidity of continental mountains give me a feeling of firmness. More than our bodies, our homes, our bridges, and our centers of world trade, these mountains will last. Just up the Columbia River from Portland is a volcanic plug known as Beacon Rock. I’ve hiked the mile up its vertical slope. At the top, you look out onto a stunning view: the whole horizon ringed with million-year-old, high-rise mountains—and a river runs through it. An informational kiosk directs your gaze up the Gorge and asks you to imagine the sight of a wall of water rushing toward you—sparing your basalt perch by only a few hundred feet. About 15,000 years ago, a series of hundred-foot floods washed through the Gorge. The water broke from the melt of Montana’s amniotic ice dams, sending a watery rush across Idaho valleys, scouring Washington’s scablands, bottlenecking through Columbia basalt, and blasting the sides of defiant Beacon Rock. The floods repeated hundreds of times. These releases from Glacial Lake Missoula’s failed ice dams would kill much life in its wake, while sculpting the land anew—a landscape that in our time fosters life in such rich abundance. The lands enjoyed here in the Holocene would be far less dramatic without these natural failures. Catastrophic floods were the architects of the Pacific Northwest.

Alan Weisman’s book The World Without Us offers an invitation to imagine earth swept of its sapiens. Weisman envisions what would happen if humans suddenly went extinct. (Stranger things have happened before.) Just picture our orphaned structures across the succeeding centuries: our canals, dams, office buildings, residences. They would crumble, “fail.” But they would also renew. One imagines birds making nests in glassless skyscrapers, groundwater refilling subways, and concrete dams going the way of Ice Age glacial dams. Amid the fragility of humanity and our creations, Earth abides.

OR DOES IT?

Our sun, now in its middle age, is all the Earth needs to stay bright and warm. This burning dynamo is mighty: you could fit well over a million Earths into the sun. But in its old age, our sun will one day expand into a red giant, engulfing the Earth and other planets, just as predictably as previous suns have done before. (Fortunately, this won’t happen for another five billion years.) In this phase, sturdy planets of gas and rock and everything left on them will fail. Then finally, our mighty sun will fizzle itself to an Earth-sized ember—all against the silence of a stopped heartbeat. The motif follows us from cells to buildings to planets—to even this solemn solar scale.

I’M ARRESTED BY deep-space photographs taken by our most recent telescope. These deep gazes depict terminal stars expanding outward toward their collapse: the nova (a small star’s thermonuclear death rattle), and the supernova (the cosmic thunder of the biggest). Even in daytime, stars are exploding through the silent night beyond. And the photographs show something else: atoms remaining in the void, nebular wisps twisting into cell-like circles and double-helix constellations—some certain to form suns delivered from the darkness of vast stellar nurseries. There is a grandeur in the view from here. For our still-expanding cosmos promises new patterns waiting to be formed, whole new worlds waiting to be born.

LARS ERIK LARSON has taught literature and writing at UP since 2005.

More Stories

Lift Up Your Harps

Mo Briare ’92, ’04 has been a nurse, a musician, and a composer of sacred music. Now she’s teaching nursing students to use music for the health of their patients and for their own health, too.

- Story by Jessica Murphy Moo