FALL 2024

In the Words of My Grandfather

A historian tracks down a stray thread of his family history in a Swiss archive.

- Story by Peter Boag ’83

I SAT IN the Federal Archives of Switzerland on a rainy spring morning in 2013, waiting for the archivist to approach my worktable. As a professor of American history, I’d explored the contents of many an aging archival folder, but this one was personal. And, I’d recently learned, it possibly involved a crime.

My grandfather, Gustav Horand, came to the US in 1917. He died before I was born. None of my family members, including my mother, had ever been able to tell me why he left Switzerland during the War. Switzerland had been neutral, but I also knew that times were difficult there given that it is a very small, mountainous country and was surrounded by belligerents. But what were the exact events and personal decisions that led to Grandfather’s departure? I needed to know.

Mom could relate the story of her father’s initial days in America, how he had trouble even ordering food in English. As the story goes, he pointed at “ham and eggs” on the menu, learned to say it, and always ordered it. Was it his favorite meal, or just the one he knew? Grandfather eventually became proficient in English, and since Grandmother was American-born, very little Swiss-German was spoken in my mother’s childhood home. And thus, much like Grandfather’s migration story, the language of a man whose DNA flowed through my veins was also lost to me. I realized very early that any hope of knowing Grandfather demanded that I learn his mother tongue. I have struggled with German since. In desperation, I even secretly tried out advice that Mark Twain offered to the disheartened student in his hilarious 1880 essay, “The Awful German Language.” “German books,” the American humorist imperiously claimed, “are easy enough to read when you hold them before the looking-glass or stand on your head—so as to reverse the construction.” Sadly, even those experiments did not yield the results I had hoped for. With my faulty German, I did make several trips over the years, beginning in 1984, to local Swiss archives to conduct genealogical work, mostly in church registries dating from the Reformation.

While I discovered baptismal, marriage, and death dates for countless ancestors, those never revealed the more soulful answers that I sought about Grandfather.

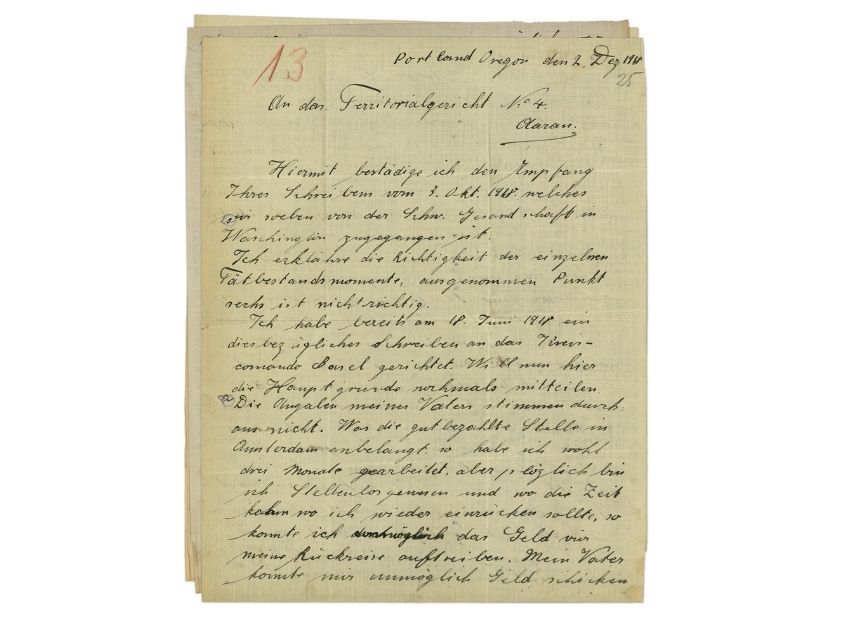

Now, in the Swiss archives years later and in the folder placed before me, were records of Grandfather’s court-martial and a warrant for his arrest. It seems he had failed to appear for prescribed military duty in 1917. This was undoubtedly a serious offense. For years every able-bodied Swiss man had to perform such service. During a time when war raged just beyond all of Switzerland’s borders, being absent without leave must have been especially egregious.

Buried deeper therein, however, was something much more: a three-page, handwritten letter in German that Grandfather composed in 1918 in Portland. It answered the charges against him and detailed his reasons for leaving Switzerland, first for Amsterdam, and then America. “Since the outbreak of the war,” Grandfather explained, “my parents have struggled in the worst circumstances,” and even depended on local welfare, something “that was for my parents as for me very unpleasant.… [E]ven with a huge effort on my part, it was impossible to find a job in the homeland. Only reluctantly…did I leave Switzerland.” In Amsterdam, and after losing an initially good job, he found “a poorly paid position on a ship bound for the West Indies. I hoped that I would soon be back in Europe, but the ship did not return, but rather stayed” in America. Through later research, I learned that only a couple days after his ship landed in New York City, subsequent to steaming to the West Indies, Germany declared unrestricted submarine warfare in the North Atlantic, and Grandfather’s ship, like many other European vessels, remained in the Americas. Unable to return for Swiss military service in a timely manner, Grandfather became a fugitive.

At the moment I discovered the letter that my grandfather penned in 1918, it seemed less a defense of himself and more a cache of clues that, as Mark Twain’s looking-glass would have it, reflected back to me information about how I came to be. For in that letter, Grandfather related not merely the effects of a world-shattering war, but the string of unlikely events that resulted in my existence: the struggles of his parents, the desperation that unemployment can cause, the fate of some forgotten ship in the North Atlantic. In my grandfather’s German words, I came face to face with a man I had never met but one who bequeathed to me the incredible gift of life. Feelings of both sadness and joy swept over me as I read the words of my grandfather, in a language I had struggled for so long to understand.

PETER BOAG ’83 took courses in history and German on The Bluff. Today he teaches history at Washington State University in Vancouver.