FALL 2024

Work & Meaning

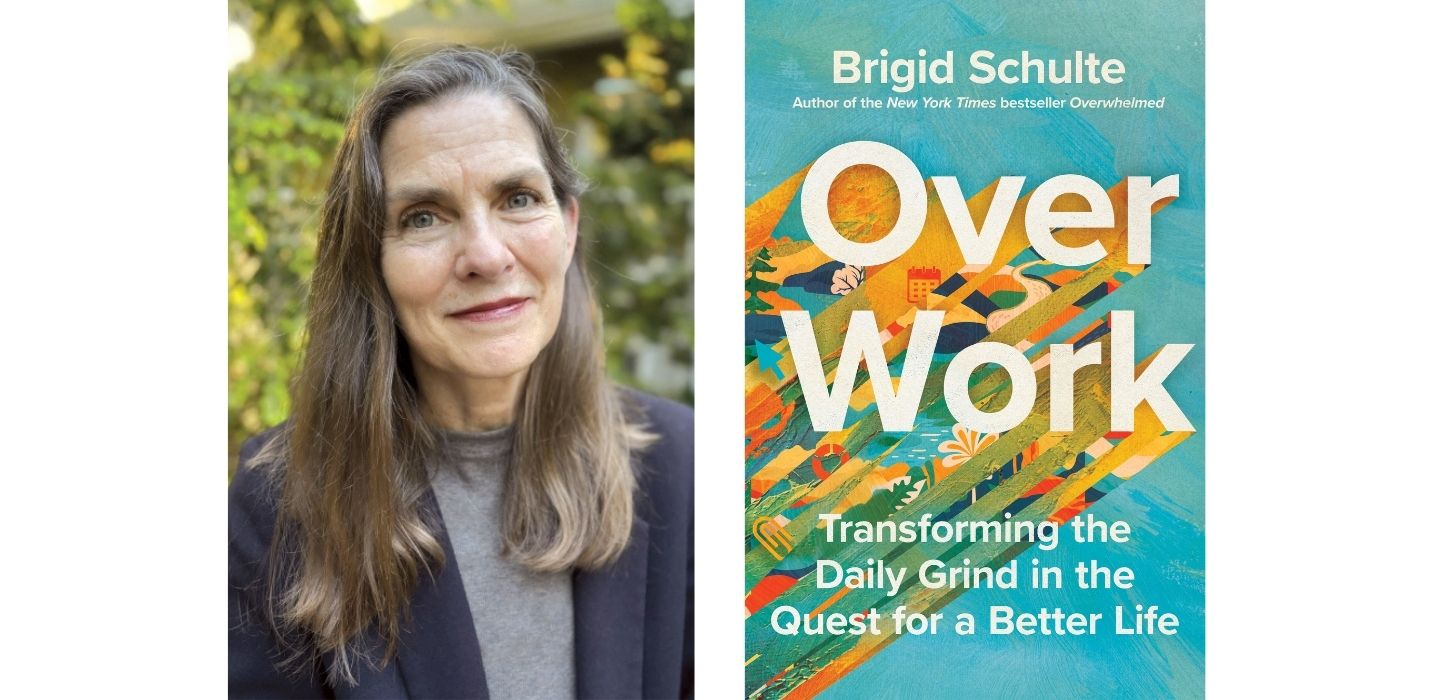

Editor Jessica Murphy Moo sat down for a conversation with Brigid Schulte ’84, hoping to dig into some of Schulte’s takeaways after 10 years of researching America’s relationship to work.

In your chapter on workaholism, you mention that the lack of health and wellbeing policies are at the root of workaholic culture in the US. How do the stories we tell ourselves about work encourage this culture?

In the United States, we often talk about the Protestant work ethic. Unless we’re Native American, we’re all essentially immigrants whose families came here seeking a better life. That restlessness has always been part of the American character, the idea that we’ll always be better, and it will be better for our children, and if we work hard there will be reward. That drive for innovation, that drive for the next best thing—it’s part of our DNA as Americans.

Because we have this rugged individualistic culture, we don’t have a lot of the kind of public policies that help people combine work and life that other countries with peer economies do. We don’t have paid family leave and we don’t support child care or care infrastructure. We don’t help people combine work and care.

And the stakes are really high. We don’t have guaranteed health insurance. It’s all tied to your job. You need a job to live, to support your health. So the way we’ve interpreted the Protestant work ethic has become part of this overwork problem that fuels workaholism.

Has working on this book—what you’ve learned—changed anything about how you work?

I don’t pull all-nighters anymore. I go for walks. I find time in my day to meditate or reflect. I really make time for joy and connecting with friends and family. Rest, recovery, joy, leisure—it’s just become even clearer how important that is.

It’s also given me a much greater awareness of the bigger picture. I think it’s helped me blame myself less, and it’s helped me see that there’s not something broken in me or that I’m the only one doing this. I am part of a larger story. And a lot of us are struggling. I’ve got my own internal drivers. I struggle with perfectionism, procrastination, and thinking “it’ll never be good enough.” But I also live in a culture that rewards the overdoing. I’m rewarded for the things that also burn me out, even if I can say that I love what I do.

From your vantage point, how has the pandemic reshaped our conceptions about work? Do you think the changes might stick?

I hope so. I don’t think we know right now. Overnight, that American ingenuity came through. People figured out how to do stuff. And essential workers, who had been invisible, all of a sudden became visible. We really do need the people who deliver stuff and stock our shelves. Remember people banging pots and pans thanking health care workers who were always overworked and undervalued and understaffed? There’s a lot that we’ve seen that we can’t unsee. But right now things are very muddy.

What I argue in the book is that we have a real opportunity to change work and life for the better. I’m very hopeful. There isn’t one way to do it. There isn’t a pill. Iceland, for example, shortened their work week. But there isn’t one-size-fits-all. I talked to police officers and child care workers and business owners and what was fascinating is they went down to that unit level, figured out what was most important, what was the most effective way to get to their desired result, and then they experimented. They ended up finding that it was about getting clear on the result that they were after—and not rewarding effort like we do. These small units came up with all sorts of different ways to do things.

It’s been so interesting to look at what drives work and overwork or toxic work at the individual, organizational, and then the larger public policy or cultural level. And then to consider what are the levers for change at each one of those levels? How can we reimagine work?