SUMMER 2024

Now Live! from KDUP

After a tumultuous few years, UP’s beloved radio station is back on the air. The joyous occasion sent us to the archives in search of its compelling history.

- Story by Rachel Rippetoe

IN MID-MARCH, Director of Student Activities Jeromy Koffler announced a comeback for the ages, one accomplished after a years-long battle with toxic mold, faulty wiring, firewalls, configuration settings, painting mishaps, and scheduling conflicts: KDUP College Radio was back on the air.

At the time, there was just one song playing over and over on the KDUP website stream, something by indie artist Gregory Alan Isakov. There were no DJs yet, no voices crooning over a microphone, no clever show titles, and likely very few listeners. But it took years of hard work to get here, the college radio station’s general manager Molly Dinsmore ’25 said.

“The buildup has just been insane,” she said. “It’s kind of crazy because for such a long time, at least for as long as I’ve been a part of KDUP, we’ve been underground and no one knows that we exist or no one knows what we do.”

The significance of KDUP’s revival might be lost on current UP students. The 73-year-old radio station has been on hiatus since 2020, when hazardous black mold was found in its former campus home, affectionately (and appropriately) known as “The Shack.” Dinsmore, a junior, admitted that, despite years focused on keeping the lore of KDUP alive, neither she nor the seniors on her staff actually knows what a functioning college radio station looks like.

“No one here has experienced KDUP on air at all,” she said.

But for those like Koffler, who has been with the University since 2003, the moment is both monumental and extremely typical of KDUP’s larger story.

Founded back in 1951, KDUP has endured near-constant setbacks. The station is a scrappy underdog on campus, hardly ever fully funded, mostly left alone by administrators and faculty. But through lightning strikes, fires, FCC complaints, various venue changes, and technology mishaps, KDUP has survived and remained integral to campus, even when no one was actually listening, Koffler said.

“They’re a story of resilience,” he said. “They keep getting hit with all these things and they keep trying to push the technology. They never want it to die. KDUP is too important to the UP community to not survive.”

Live from UP

Radios first earned club status at UP in 1937, through a group of students nicknamed the “hams,” who, according to The Log, were able to send communications to 36 countries via short-wave radio. In truth, their greatest achievement might have been reaching UP’s football team while playing in Butte, Montana.

It wasn’t until the spring of 1951 that a radio broadcast entered the UP airwaves. The Beacon reported on May 18, 1951, that KDUP, the new “Voice of the People,” had launched with a day-long broadcast from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. over campus loudspeakers. Throughout the day, the station’s student-led staff spun records, read news and sports reports, performed drama skits, and gave away prizes.

The station began broadcasting regularly in October out of the third floor of Howard Hall, the former sports building that was situated where Dundon-Berchtold Hall now stands. Programs aired from 2 to 4 p.m, and the AM station could only be heard near campus. KDUP aspired to be a professional broadcast, playing classical music and show tunes but also “ripping and reading” from a United Press teletype, which would fax in news scripts from wires like the Associated Press that DJs could read on the top of the hour. Students also hosted an interview show called “Your Life,” interviewing popular campus personalities.

Just two years after its debut, the station was already marked by its scrappy resilience. The 1953 yearbook described KDUP as an “infant radio station” experiencing “growing pains, mostly headaches.”

“Though the station operated with just 10 watts, the operators contented with ten watts worth of trouble,” The Log read. “But aided by a smiling ‘Dame Fortune,’ the studio produced successfully every broadcast. Right now, KDUP, the voice of the University of Portland, speaks in a whisper, but its lungs are growing stronger.”

The following year, KDUP won fifth place in a national newscasting contest for its professional news broadcasting style. By 1957, the station had earned more space, moving from “cramped quarters in Howard Hall to a soundproofed five-room suite in Music Hall,” according to The Beacon.

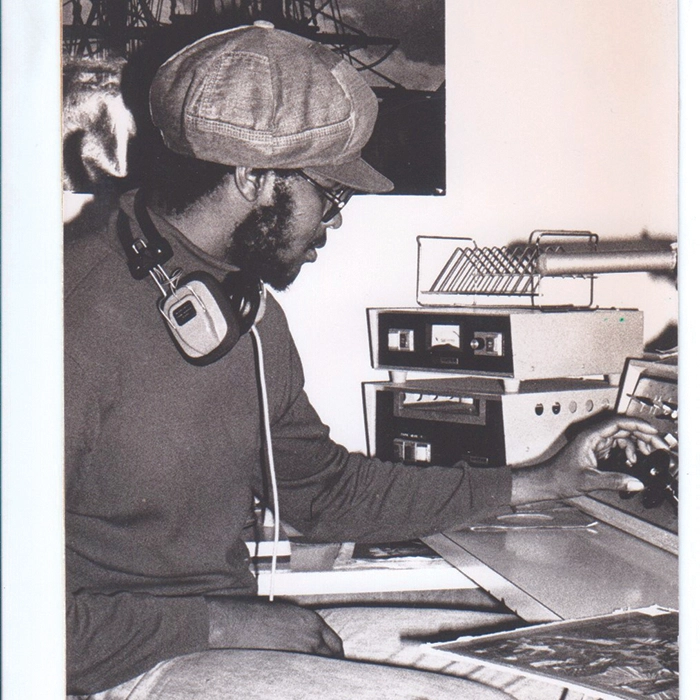

Leonard Williams at the KDUP soundboard in 1977.

Don Baldrica, Diane Della Santina, Don Haynes, Norm Creitz in the KDUP studio. Photo from "The Log" yearbook, 1954.

In the late ’50s, the station had “a rapidly growing record library” with “enough records to play 24 hours a day for seven days without repeating or without a break,” The Beacon wrote. Positioned in the campus Music Hall, a bare-bones army surplus building built during World War II, the station no longer broadcast on short-wave but through a carrier current system, which was essentially an underground intercom system. “There were wires running from the broadcast booth to small transmitters in each of several dorms,” said Franz Schneider ’63, who was a DJ in 1959. “The transmitter had a radius of about maybe 150 feet. Very limited."

Franz and his wife, Mary (Pajalich) Schneider ’63, who was also a DJ, said the station was run in those days by Fr. Robert Beh, CSC, who was known as the best-dressed priest on campus. “They all wear the same outfit, but he was somehow dapper,” Franz said.

Father Beh took the radio seriously, requiring students to get an official operator’s license and monitoring all the shows.

“I think that Father Beh figured if people wanted to listen to Rock and Roll, there were a number of local radio stations for that,” Franz said. “He had his way about what would be allowed on the air and what wouldn’t.”

Franz said his time at KDUP, where he hosted a half-hour program called “Classical Keyboard” playing piano and organ music, came to an end when he pulled a prank, interviewing a friend on air who pretended to be an important musician acting “outrageous and noisy.”

“Father Beh showed up, and I think that was the end of my DJ career,” he said. “He was very serious. He did not like dead air. He also did not like unprofessional conduct.”

Mary remembers keenly feeling the pressure to fill KDUP’s airwaves, even when presidential hopeful John F. Kennedy gave a speech on campus, his first and only appearance in Portland during his campaign for the 1959 primaries.

“I was scheduled to be on during that time,” she said.“And I was very conscientious, so I went on and I did the station identification and the rip-and-read news and I became convinced that nobody except me was listening to what I was doing. So I left the music on and ran out to where the speech was, only about 100 feet away.”

The speech was over, she said, but she caught the future president as he was exiting the stage, talking to reporters. She said she was shocked to see him wearing what she immediately recognized as stage makeup. She made it back to the station in time to finish her show.

“There was no dead air,” she said.“I was disappointed that I hadn’t gotten in fast enough to hear him say anything, but that was my adventure.”

The Fight to Be Heard

By the late 1960s and early ’70s, KDUP was no longer under Fr. Beh’s hawk-eyed leadership. “There was no faculty involvement, no general oversight of us or anything,” said Tony Staley ’72, KDUP’s general manager from 1969 to 1970. “They were always very hands off. They just let us do what we wanted to do. And nobody was coming down offering us advice or anything like that. It was just kind of, ‘Okay kids, you got your new toy, now go and play around with it.’”

Ray Kolibaba ’71 agreed that the operation was very “seat of the pants.” He earned a partial scholarship his first year at the University in 1967 and offered technical and engineering assistance to KDUP. At the time, he said the station pumped its signal to just two transmitters, one in the all-female dorm Mehling Hall and one to the all-male Christie Hall. He said they’d try to crank the signal as high as they could because it often didn’t reach all corners of campus. But this posed another problem.

“It would get into the neighborhoods and the neighbors would complain,” he said. “People didn’t appreciate getting ‘free’ radio from the University. It was an older neighborhood, and the stuff we put on the air was probably not what most of them wanted to hear.”

At the time,“Light My Fire” by The Doors was the most requested song, Kolibaba remembers.

But when neighbors complained, Kolibaba said he’d just go into the dorms and adjust the transmitters. Every weekend, he would inspect them and make sure everything was running. He said he always needed an escort to inspect the transmitter inside the all-female Mehling.

Kolibaba later left to join the ROTC, and things got a bit dicey. The first thing Staley remembers happening when he became general manager of the station in 1969 is the Music Hall burning down. The University was already planning to relocate KDUP to the newly built Buckley Center, but those plans had to be accelerated as the wood barracks of the war-era Music Hall went up in flames. One positive aspect of the move, Staley said, was the station got all new equipment, a new soundboard and new mics, and the University even brought in an engineer from KGW to teach them how to use it. But the station was still plagued by its signal’s short reach, not penetrating through several of the dorms.

One day, Staley said he got a call from a high school student who lived a couple blocks off campus who said he could pick up KDUP’s signal. He called because his younger brother had a song request: “Summer in the City” by The Lovin’ Spoonful.

“And so I got to know this guy a little better,” Staley recalls. “And he said, ‘We could do some things to soup up that signal. This transmitter can put out a lot more power than it is.’” He said he and his new friend tinkered with a dipole antenna on the top of Buckley Center. Sure enough, the sound quality of KDUP drastically improved.

Then one day, men in suits showed up to his office.

“They said, ‘We’re here from the FCC and we want to know who’s in charge.’ And I said, ‘Well, I am.’ And we had to go up on the roof of Buckley and show them the transmitter and the antenna,” Staley said. “They looked at it, and they said, ‘Well, we gotta shut it down.’”

It was almost the end of the school year. The annual communications banquet was the same night, Staley remembers.“I got to go there and tell the powers-that-be what happened,” he said.“What they finally had to do was say, ‘Well geez, we gotta set this thing up legally or just shut it all down.’”

It wasn’t a huge investment, Staley said. The University eventually bought two more transmitters to wire in Kenna Hall (which at the time was called Holy Cross) and Shipstad Hall.

But issues didn’t end there. A Beacon editorial in 1982 described KDUP’s sound quality as “horrendous,” making a case to the University to buy more transmitters. Through student-led pressure and petitions, KDUP was finally allocated enough funds to buy two new turntables, a new cassette player, and three new transmitters.

Yet by 1984, the radio station was singing the blues. A Beacon article titled “Controversy continues over KDUP” quoted history professor James Covert discussing the “material and financial demise of KDUP.” Long gone were the good old days when he would grade papers and listen to KDUP broadcasting the baseball games live, Covert said.

“I’m tired of people treating KDUP like the little orphan of U of P.… The time has come for us to have a radio station—a Portland radio station,” he said. Finally in 2002, the University did away with the carrier wave system altogether. The graduating class used its Senior Gift project to fund a new antenna mounted on the roof of Mehling Hall, allowing KDUP to once again broadcast through the airwaves on 1580 AM.

The station wasn’t authorized to broadcast on that frequency, but it was chosen for its position on the end of the dial because “they felt like no one was using it,” Koffler said.

But the antenna had technical problems from the jump, needing repairs just two years later and also attracting more FCC compliance issues.

“The signal would bleed out over the river and then they would be pirate radio,” Koffler said.

Sound quality issues persisted until the summer of 2009, when communications between the station and the antenna were lost entirely. Koffler said the source of the radio silence was uncertain but likely had to do with some underground wiring that had been severed during the rebuild of the Bauccio Commons Dining Room.

With KDUP off the airwaves, the station had to fall back on technology it had fortuitously established nearly a decade earlier: its website stream at www.kdup.up.edu.

The system’s software would need to be updated several times throughout two decades, and even went off the air for several months in 2013 after lightning struck the Bell Tower at the center of campus. But the switch to streaming shepherded the station into a new era, one focused less with technical difficulties and more on KDUP’s cool factor. The station adopted a new tagline, asserting its presence on campus even as it became less audible: “College Radio is Not Dead."

Beyond Radio

When Madeline Sabatoni ’04 was promotions director for KDUP in 2003, she said college radio had become an integral piece of her identity.

“It made me feel really cool in a lot of ways,” she said. “College radio for me was an indicator of having taste. The same way that you would want to go listen to local bands. It was pre- the term “hipster.” But that’s kind of what I was going for and the college radio station and The Shack definitely fit for me.”

KDUP moved into The Shack in 1986. The house, positioned on the edge of The Bluff next to St. Mary’s, was first sold to the University in 1948. Throughout the years, it housed a range of University staff, passed from a cook to the manager of the Commons to a maintenance worker. So when the radio station inherited the dwelling, it was already lived-in and well-loved.

“It was nice to have a little hangout spot,” Sabatoni said. “A place that felt like ours even if it was a little run-down.”

By the late aughts and 2010s, as KDUP transitioned from the airwaves to streaming, this kind of space became invaluable to continuing student interest in the station, Koffler said.

“There was a time when the students who were really involved were focused on that professional development piece of ‘I want to become a radio broadcaster or I want to become a professional DJ,’” he said. “And then it became more about building community, goofing around, and playing your favorite songs.”

What Sabatoni remembers best isn’t the show she hosted but the concerts she got to see as a result of working at KDUP. As promotions manager, promoters would send her concert tickets, CDs, and merchandise to give away as prizes on air. As a graduation present, one of the promoters gifted her a pair of tickets to see Belle and Sebastian in Seattle.

A decade later, Arran Fagan ’18 found a role at KDUP through his love of going to concerts and interviewing artists, in part because he himself is a musician.

“Selfishly, I really wanted to know what musicians were doing from a creative perspective and also a functional perspective,” Fagan said. “So I was like, college radio will be great. I can interview artists and get free tickets to shows. I kind of abused the power. I would send a lot of emails to venues and artists and be like, ‘Hey, can I interview you? And then I get to go see the show?’”

Fagan started as events coordinator for KDUP in 2015 as a sophomore and then became general manager the following year. Koffler said his leadership marked a new era for the radio station. Fagan and his staff began hosting concerts on campus, and became more involved with student activities, making KDUP more visible.

“If a group of kids who play instruments or sing didn’t get involved, I can see where it might have actually died down a little bit,” Koffler said. Proving KDUP’s value to campus through a series of well-attended on-campus concerts in which indie/folk artists like Jeffrey Martin and Kris Orlowski performed, Fagan said he was able to advocate for an increase in KDUP’s funding. In the span of two years, he upped the station’s budget from $1,000 to $10,000 for events.

“We had a show in Shipstad, in Christie, in Mehling,” Fagan said. “I would slowly get bigger and bigger bands that kind of fit within the college radio sphere.”

Once he’d given KDUP a level of legitimacy on campus, Fagan said he and his staff were able to amp things up, providing a platform for a multi-day music festival called Smash the Bluff, riffing off the University’s yearly concert Rock the Bluff. The students had almost free rein on what bands performed, he said.

“We had gotten so big and we had the credibility to be able to be a little more free-form without Jeromy asking too many questions,” Fagan said. “And so we started doing these less sanctioned events and they were doing really well.”

Of course, Fagan couldn’t have predicted that the world would face a global pandemic in 2020, or that the live-music reinvention of the station would give KDUP the tools it would need to survive post-lockdown.

“They really shifted their attention to micro shows, open mics, live music performances, concert reviews, all the things that a radio station does, without actually being on the air,” Koffler said. “And that’s been able to sustain them. Which is pretty cool to see.”

Arran Fagan performs a concert at The Shack in 2018.

Weird Chaos

A few years into his tenure, Koffler remembers running from his office in St. Mary’s to The Shack in a panic. A KDUP listener had alerted him to a giveaway a pair of DJs were promoting on their show: two concert tickets would go to the first student willing to enter the studio and strip naked.

“And sure enough, there were two girls walking from The Commons that were like,‘We’re here for the tickets.’ I was like, ‘No you’re not!’” he said. “And these guys were like, ‘We didn’t think anyone would really do it.’ I’m like, I don’t care! This is a Catholic school. How did you think that was going to go?”

Most former KDUP DJs and staff have at least a story or two about college radio antics. Perhaps because the station has always been student-run, or maybe because there’s a feeling that no one is really listening—KDUP historically has never had more than a dozen or so listeners at a time—there’s always been a feeling among DJs that anything can happen in The Shack.

On a Friday night during the months KDUP was shut down by the FCC, Staley said he and a friend Pat Cashman ’72, who actually ended up going into radio professionally, had an idea to go back on the air after a drink or two. Some promoter had sent the station a record of the audio for the 1970 movie Joe. Staley and Cashman decided to open up the station in Buckley and start playing it.

“We just did it spur of the moment, and suddenly we start getting phone calls and everything,” he said. “It was kind of fun. We played some music too, and we didn’t use our real names because we didn’t want to get in trouble.”

A few months later, Staley said he and Cashman got a phone call in their dorm from someone identifying themselves as the Dean of Students, who was familiar with the unsanctioned broadcast and very unhappy about it. Cashman, who had just accepted a position as editor-in-chief of The Beacon, was terrified the stunt had put his job at risk, Staley remembers.

“Pat is starting to get these cold chills, like he’s going to lose this new job and lose his scholarship and everything,” Staley said. “So we’d pass the phone back and forth to each other trying to talk to [the dean] until we realized it was a friend of ours and he was just pulling our legs.”

That they got away with it really only encouraged them. Staley says there was a feeling that while broadcasting into the ether at KDUP, you could get away with anything. “You can’t deny the written word,” he said. “But radio.… Nobody ever recorded anything we did.”

Fagan said he often had to remind his DJs that they should behave as if people were listening. Once he had a mother of one of the DJs call to complain that the jockeys before her daughter’s show had been smack-talking her.

Leaning into all kinds of weird chaos is what made KDUP such a unique place on campus, Fagan said.

“It really was just a wonderful kind of chaotic mess for people trying to figure out who they were,” he said. “It was a community that I’d always wanted and never had in my small town. I had felt like a person that had never really found a place. And so I felt very at home there, and we kept coming across people who had yet to find their group, but when they saw a KDUP show or event, it was kind of like a light bulb went off for them.”

KDUP hosted Smath the Bluff again this spring; Zyanna was among the featured musicians.

Rising from the Ashes

During her freshman year, Molly Dinsmore emailed KDUP’s general manager asking to get involved without even realizing it had once been a functioning radio station.

“I just thought that they put on concerts and that was it,” she said. “I didn’t really know that it was ever a running station or that it could be again or that that was a goal.”

But now, as general manager, Dinsmore has spent over a year working towards getting KDUP back on the air.

After a leak developed in the roof of KDUP’s beloved Shack while the campus was empty in the spring and summer of 2020, black, toxic mold developed on the ceiling and along the walls of several rooms. Some equipment and the majority of the station’s CD collection were saved, but nearly all the albums, cassettes, and 8-tracks stored in The Shack were not able to be removed. “They’re all just sitting there, but you can’t go in there without a hazmat suit,” Koffler said. “It’s weird because I could literally walk over there myself right now and rescue these albums because who knows how valuable they are. I had no idea what KDUP’s collection consisted of, but my impression is that it was stuff that was irreplaceable.”

Although Staley admitted that, at least in 1969, most of KDUP’s record selection was “garbage,” it wasn’t just history lost with The Shack’s condemnation, the station no longer had a home to host shows.

KDUP temporarily moved over to a streaming site called Twitch, where DJs streamed playlists. But this threw the station back into familiar trouble—this time, not with the FCC, but with Spotify.

“[The DJs] weren’t getting access to the studio, to their music, so they just started using their own Spotify playlists, which is completely illegal,” Koffler said. “Twitch and Spotify were having fights back and forth and they were like, ‘No, this can’t happen,’ and so they got shut down again.”

In the spring of 2021, Student Activities worked with Residence Life to allow KDUP to move into a few study rooms in the basement of Kenna Hall. But the transition has been a slow one. A local radio engineer helped staff identify some necessary equipment and software upgrades and soundproof the rooms in Kenna, but in the summer of 2022, the engineer abruptly retired. Then an engineering adjunct volunteered to help the station get back online, but Koffler said his contract with the University wasn't renewed.

“Every time we get a little momentum going, something upsets it and then we have to regroup and start again,” he said.

Finally, in the fall of 2023, with increased funding, KDUP began buying up music on iTunes, and staff members began training on its new automation software Zetta/GSelector.

“It’s a very legit radio technology that you would find at a normal radio station in downtown Portland, which is really cool,” Dinsmore said. “My staff and I have been training for almost two years on it.”

Dinsmore and her team have begun getting the word out that students will soon be able to host real radio shows again. The biggest hurdle so far, she said, is that Kenna is a dorm, where only residents have key card access. And with KDUP finally going live at the tail-end of the school year, she said the station won’t have a full roster of shows until next year. But the interest is there.

“I’ve had professors reach out to me. I’ve had The Beacon reach out to me,” she said. “They really care about the radio, they care about the fact that we’re on air again, and that’s awesome.”

Koffler said students will always love KDUP. It represents a shared love of music, a shared desire to know what’s cool, what to listen to next.

“There’s people who really have found meaning in KDUP, like if KDUP didn’t exist, I think there would be students that would leave the University,” he said. “It’s a bunch of people who just accept each other for being unique individuals who have different tastes in music and there’s no judgment in KDUP because it’s kind of a cool thing to do.”

RACHEL RIPPETOE ’19 is a journalist based in New York City. She writes full time for legal news publication Law360. She has also contributed to publications such as City Limits, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Juvenile Justice Exchange, The Imprint, and U.S. News & World Report. She writes a weekly newsletter about television and culture.