WINTER 2024

New Causes for Hope

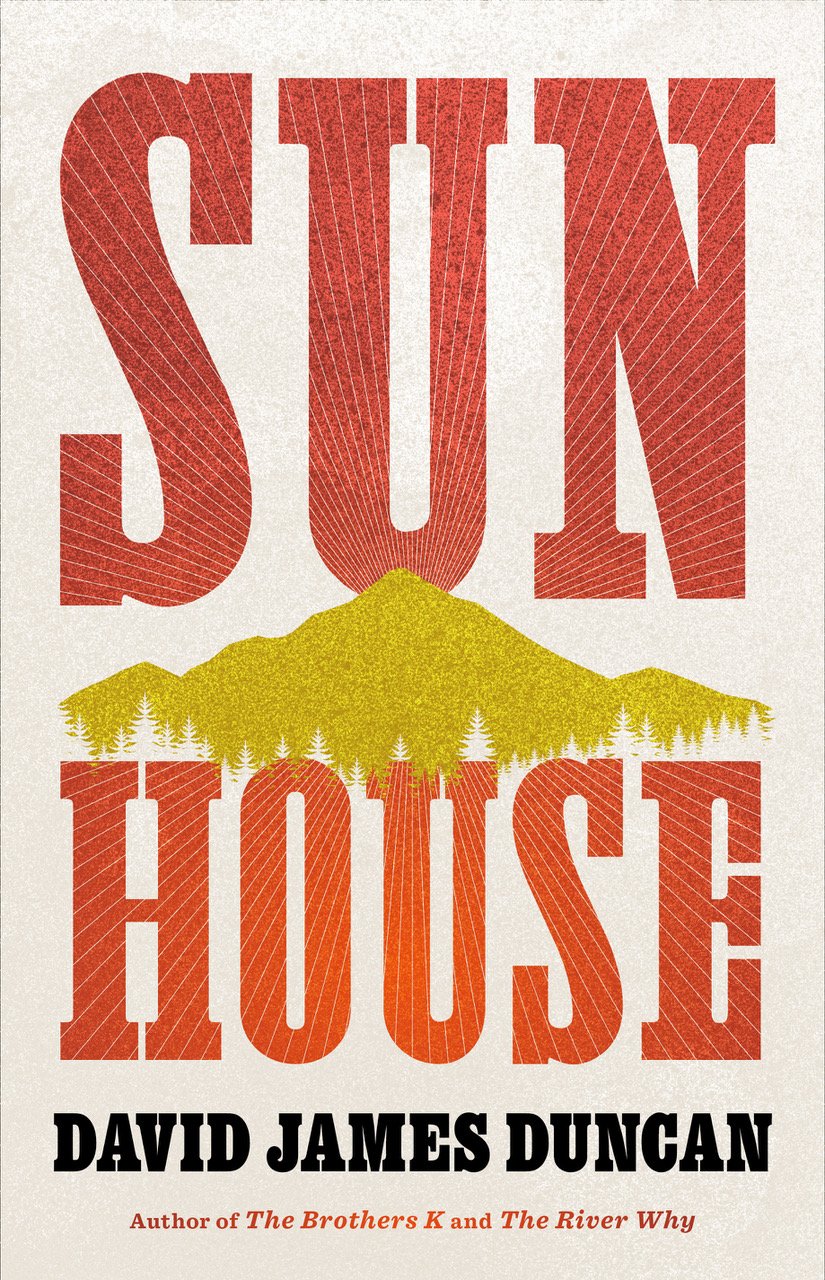

UP alum Sam Mowe ’22 sat down with author David James Duncan to discuss life and his new book.

READERS OF DAVID JAMES DUNCAN’S first two cult-classic novels, The River Why (1983) and The Brothers K (1992), had to wait 31 years to bask in Sun House, his third novel, published in 2023. Like his earlier novels, Sun House tells the story of an epic search for meaning and wisdom in the American West. This time, however, some of that search takes place on The Bluff. Born in Portland in 1952, Duncan lived in Oregon for forty years before moving to Montana. Duncan often gives credit to his many literary and spiritual friends, and in Sun House’s acknowledgements he includes the previous editor of this magazine, Brian Doyle. After telling me that he’s more articulate with his fingers than his tongue, Duncan and I recently enjoyed a warm email correspondence about Sun House during the darkest days of the year.

READERS OF DAVID JAMES DUNCAN’S first two cult-classic novels, The River Why (1983) and The Brothers K (1992), had to wait 31 years to bask in Sun House, his third novel, published in 2023. Like his earlier novels, Sun House tells the story of an epic search for meaning and wisdom in the American West. This time, however, some of that search takes place on The Bluff. Born in Portland in 1952, Duncan lived in Oregon for forty years before moving to Montana. Duncan often gives credit to his many literary and spiritual friends, and in Sun House’s acknowledgements he includes the previous editor of this magazine, Brian Doyle. After telling me that he’s more articulate with his fingers than his tongue, Duncan and I recently enjoyed a warm email correspondence about Sun House during the darkest days of the year.

The city of Portland is the center of gravity in the first half of Sun House. Can you tell me about your connection to Portland?

I was born in the old Seventh Day Adventist hospital on Mount Tabor in Southeast Portland. I grew up out in Northeast, attended Portland State, and lived in several Portland neighborhoods during my forty Oregon years. Living in Portland I grew to love the way its neighborhoods are almost discrete “small towns.” I lived on a small farm in Southeast on Johnson Creek, in which to my amazement I caught a few steelhead. I grew to love the Belmont district through friends who lived there, enjoyed the transformation of North Portland from its years as “the Swan Island shipyard neighborhood” to the cosmopolitan and very diverse North Portland of the ’90s, and spent my last six Oregon years in Northwest so close to Forest Park that blacktail deer browsed in the yards and a ruffed grouse once flew through an open door into our living room. But throughout those forty years, I longed for proximity to what poet Gary Snyder called Mountains and Rivers Without End. In many ways I feel that Sun House celebrates the depth of my relationship with exactly that. The move to Montana and the banks of a trout stream also created a wonderful place to raise my two daughters, now in their early thirties, both of whom love nature as deeply as I do.

In Sun House’s bibliography—a rarity for a novel—you list the many books that have helped you to pursue a contemplative life. Can you tell us more about what your spiritual life looks like in practice? Is there a character in the novel that is most like you in this regard?

To answer your second question first, Jamey Van Zandt echoes my physical being. I had a hernia when I was 15 months old and had to learn to walk twice. Jamey also manifests the anger I felt toward God when my older brother died a long, slow death from a heart defect when he was 16 and 17, just as Jamey’s mother suffered a lot before she died. But in spiritual matters it’s Risa and me who are alike. Eastern spiritualityand practices, and the mystical strain of all world traditions, began to wow me at age 16.

As to your first question, the magic of a practice in my experience is that day in and day out; it’s a matter of mundane discipline. But once in a rare while, at its best, a practice opens unto mystery by enabling us not to find the self, but to forget the self. To think you’ve found the self is to reduce self to a mere thought, just as we do when we claim to understand God. When the over-glorified René Descartes said, “I think therefore I am,” he flattened our human essence into the kind of two-dimensional smugness we hire meditation teachers to help us erase. Compare Descartes’ five words to five from Jesus: “Before Abraham was, I am.” Jesus saw Descartes coming 1600 years before he arrived! This sentence radiates the essential wonder of human existence—and buries Descartes’ arrogance in a well-deserved grave!

Again in the novel’s bibliography you write “that light shines brightest out of darkness explains why so many seekers are finding new ways into solace.” What are some of these new ways of spiritual expression, especially those taking shape in response to what some are calling Earth’s sixth mass extinction?

We’ve all got two mothers, the woman who gave birth to us, and Mother Earth. I find that my despair over being a partial cause of the sixth great extinction simultaneously reminds me that Mother Earth has endured five greatextinctions that we know of, and restored epic biodiversity to the planet all five times. There is no question in my mind that she will do the same a sixth time—but at her own regal pace. What’s in question is how many members of our troublesome species will survive Earth’s regal pace.

Even so, the discovery of remarkable new causes for hope has picked up greatly. For instance, the relationship between ancient forests and the intertwined mycelium network below them has shown us great Mother Trees ruling forests who are nearly as amazing as the tree people in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. At the end of their lives my friend Barry Lopez and the Oregon poet Tom Crawford separately arrived at the conclusion that the exemplary new model of how humans in the coming age of the world need to learn to behave are the great murmurations of starlings. Via the individual bird’s reflexive focus on the five or six birds closest to it, it never crashes into another starling. Peregrine falcons diving through murmurations at 180 miles an hour often fail to make a single kill and have to settle for a dinner of mice or voles.

The community that forms in the novel’s Elkmoon mountains of Montana is not an intentional community but an “unintentional menagerie.” Why is that an important distinction?

An unintentional menagerie leaves room for grace or wonder to slip into the human attempts to live in harmony. Mother Teresa helps us here. A revealinginterview between her and CBS newsman Dan Rather went like this:

Dan Rather: What do you say to God when you pray?

Mother Teresa: I don’t say anything. I just listen.

Dan Rather: Well, what does Jesus say to you?

Mother Teresa: Oh, he doesn’t say anything either. He just listens.

This is the polar opposite of intentionality’s “road to hell.” We can enter into mystery with an old woman satisfied to sit with her Unseen Lord, feeling him listening as faithfully as she herself is listening.

In an earlier email you mentioned that Sun House celebrates the depth of your relationship with “mountains and rivers without end.” Can you say more about that relationship?

My lifelong home turf, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana, are a weave of weathery forces, flora, fauna, and wild intricacy to which people from all over the world flock like grateful birds simply to see earth being earth; see wildness intact; see the earth dreaming up beauty. Today we call these places ours, but the northwest and northern Rockies are a weave of life-forms and mysteries we did not create, and cannot re-create once the wild’s ability to weave is ravaged. These great regions were pre-American and will be post-American. They are what enable biodiversity to diversify, natural selection to naturally select, and generation aftergeneration of kids to muck around in river shallows with frogs, fingerlings, and caddisfly casings. And these regions are governed not by such creatures as “governors,” but by elemental and celestial harmonies as powerful as earth’s spinning yet as intricate as an orbweaver’s dew-bedecked web.

These places and forces, to put it the ancient way, are our Mother, the living terrain her body, the flora her clothes, the lakes, rivers, rills her blood and arteries, the seasons and weathers her moods, the birds, fish, fauna, humans, all, equally, her offspring. And every man, woman, and child striving to defend her life and the lives she supports—even in poverty or political impotence, even against seemingly hopeless odds—is not only a hero but an integral part of her, hence every bit as holy as she whom they seek to defend.

SAM MOWE (Nonprofit MBA ’22) is the publisher at Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.