Each room in Dundon-Berchtold Hall has a unique crucifix, brought here by University of Portland faculty, staff, and students who have found meaningful relationships and experiences in these places around the world. Learn more about the individual stories behind these crosses.

photos by Adam Guggenheim

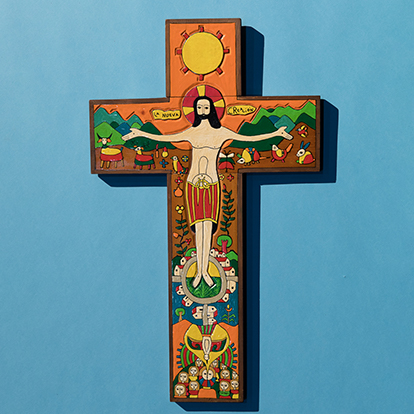

I was accompanying students and members of the Campus Ministry staff on a pilgrimage to El Salvador in May 2019. I found the crucifix in a shop run by a collective of indigenous artists who are striving mightily to resurrect the arts of the region and who are committed to fair trade practices and compensation for artists. This crucifix is filled with bright colored enamels typical of the art style of the region. The Christ figure is surrounded by village children and their parents. Its vibrancy drew me at first, and I love the communitarian dimension of it: we are all the Body of Christ, sharing in both the crucifixion and the resurrection we are sure to experience. Being in El Salvador was completely overwhelming, but the stunning, bright colors and artistry on display in these crucifixes convinces me that the people of El Salvador know they are holy, beloved of God, and resilient in ways I can barely fathom.

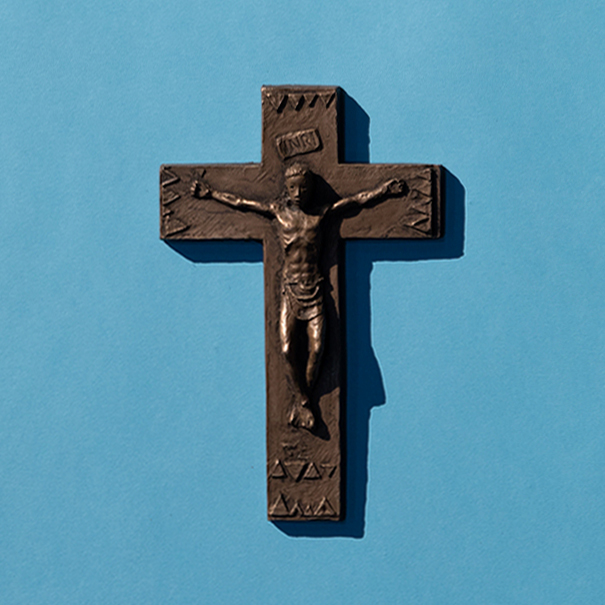

I was the primary accompanier for the Moreau Center civil rights immersion, where I found the crucifix. For the several days we stayed in Montgomery, Alabama, we were hosted by Resurrection Catholic Church and Resurrection Catholic Missions. The Church membership is mostly African American and is pastored by Fr. Manuel Williams, CR, who is African American himself. The crucifix has African American features and was beautifully sculpted by a Polish sculptor, Wiktor Szostalo, with bronze, wood, and stainless steel materials. It’s beautiful that a black person can “see their face” in Christ’s, when we rarely experience representations of Jesus that are not Caucasian-centric.

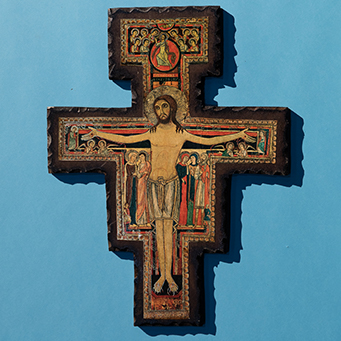

We had just completed the University of Portland pilgrimage in France in July 2018 and then took a trip to Assisi, Italy. St. Francis adopted the Tau cross as his personal sign, and it is now the symbol of the Franciscan order. The Tau cross is shaped like the Greek letter Tau, hence its name. The Tau crucifix is made from olive wood, which grows abundantly in the Umbrian area of Italy, where Assisi is located.

I was accompanying the new social justice immersion to Tanzania that I developed in collaboration with Mwenge Catholic University and Holy Cross parishes in Kitete and Sombetini when I purchased this cross. We really liked the image of the hands and the Holy Spirit. I don’t know who the artist is nor the material it is made from, though it is wood, and someone said that the black wood is indigenous to the area. The image makes me think of the many hands we touched during our time in Tanzania and that the experience was guided by the Holy Spirit for sure. So many things that happened and were possible were just pure grace.

I was in Arizona as part of the Moreau Center for Service and Justice border immersion. We visited the Tohono O'odham Nation, which occupies tribal lands in Southwest Arizona. The cross was found at Mission St. Xavier de bac, located on the Tohono O'odham Nation Reservation about 10 miles outside Tucson, Arizona. The mission was founded in 1692, and the church was built in 1783. I chose the cross because it was made by a local artist from the Tohono O'odham Nation and because it illustrates the strong influence and melding of indigenous, mestizo, and Mexican styles you see in the region. I appreciated the cruciform being represented as a bird as a representation possibly of peace, but even more so the connection between spirituality and the natural world.

Karen Eifler and I went looking for a crucifix at St. John’s University in Minnesota during our stay there in June 2019 for the Collegium, a Colloquy on Faith and Intellectual Life. I was struck by the deep roots of the Benedictine order at St. John’s. Many of the architectural elements on the campus reflect these roots, including the beautiful abbey church with a honeycomb pattern that is echoed across the campus. The crucifix we found on campus also echoes the symmetry and the order of St. Benedict. Clean lines, simple and elegant geometries, with beautiful details. The wood of the cross comes from the land near the campus, and it was crafted by one of the brothers on campus. Many of my favorite parts of Jesus’ life and teachings are captured beautifully by the Rule of St. Benedict. Both humility and the importance of listening are very important in the Order, and both are uniquely challenging to most of us in modern times. The crucifix from St. John’s will always remind me to both listen carefully and to seek balance.

This cross was a gift to University of Portland from the late regent Earle A. Chiles.

I found the crucifix at St. Mark’s Basilica (San Marco) in Venice. I traveled with my husband and three kids during a weekend while teaching in the summer Salzburg program. My husband and I had both been to Venice before, but our kids were very excited to visit the city of canals. Our favorite part of that trip was visiting the Doge’s Palace in the evening after the crowds had thinned, and we nearly had the space to ourselves. Around 9 p.m., we looked out the window of a second floor room and watched the lunar eclipse — it was quite spectacular.

I found the crucifix in Cuenca, Ecuador, when I was teaching in the UP study abroad program in Quito. On a free weekend, I visited Cuenca from Quito, which is an hour flight south. I bought the crucifix at a shop connected to an anthropology/archeology museum in Cuenca. Cuenca is a very traditional city, and the museum gave us a great feel for the traditional culture of Ecuador. I felt that the crucifix represented that tradition — a mix of indigenous Ecuador and Catholicism. The style of the cross is one you see throughout Ecuador, especially in Cuenca and the south. This cross helps me to think about the relationship between Catholicism and places in the Western Hemisphere that it has spread to. At times this relationship can be a colonial one, with Catholicism overwhelming indigenous traditions. But at its best, Catholicism merges with, enriches, and allows for new expressions of indigenous values and skills.

I was spending my second summer in Italy studying opera when I found the crucifix in Bologna. I visited Santo Stefano, a beautiful complex of around five different chapels, a crypt, and a cloister. I knew that I wanted something to help me remember Santo Stefano, and I had it blessed by a priest. During my time in Italy, Santo Stefano — an ancient, sacred place — was one of the churches I could count on to center myself in the midst of the constant movement of the performance world.

We had just completed the University of Portland pilgrimage in France in July 2018 and then took a trip to Assisi, Italy. This crucifix has a strong connection to St. Francis of Assisi. St. Francis is said to have been praying before the San Damiano crucifix when he received the “commission from the Lord to rebuild the Church.”